NEWS

|

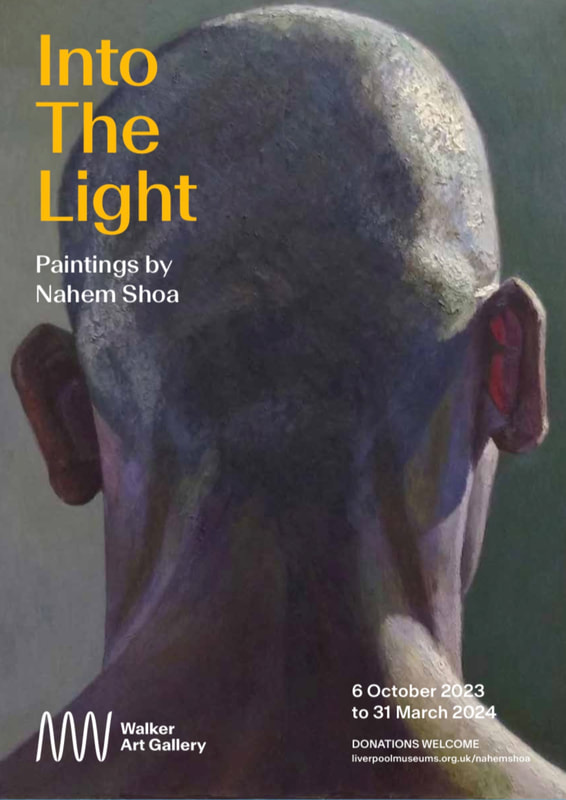

Into the Light: An Intervention by Nahem Shoa 6 Oct 2023--31 Mar 2024

Into the Light will see six of Nahem Shoa’s paintings displayed beside famous artworks from the Walker’s permanent collections – including artists such as Joseph Wright of Derby, David Hockney, Lucien Freud and James Tissot. Asking uncomfortable questions related to Transatlantic slavery, Liverpool’s cotton industry and the objectification of women in art, Into the Light will see six of Nahem Shoa’s paintings displayed beside famous artworks from the Walker’s permanent collections – including artists such as Joseph Wright of Derby, David Hockney, Lucien Freud and James Tissot. Shoa’s intervention also celebrates the Walker Art Gallery’s newest acquisition by the artist, The back of Gbenga Ilumoka’s Head. This ground-breaking and provocative painting is part of Shoa’s pioneering body of work around themes of race, identity, diversity - and the importance of celebrating British multiculturalism. |

Artists & Illustrator's Magazine January 2024 - Into The Light at Walker Art Gallery mentioned as one of the best exhibitions in UK.

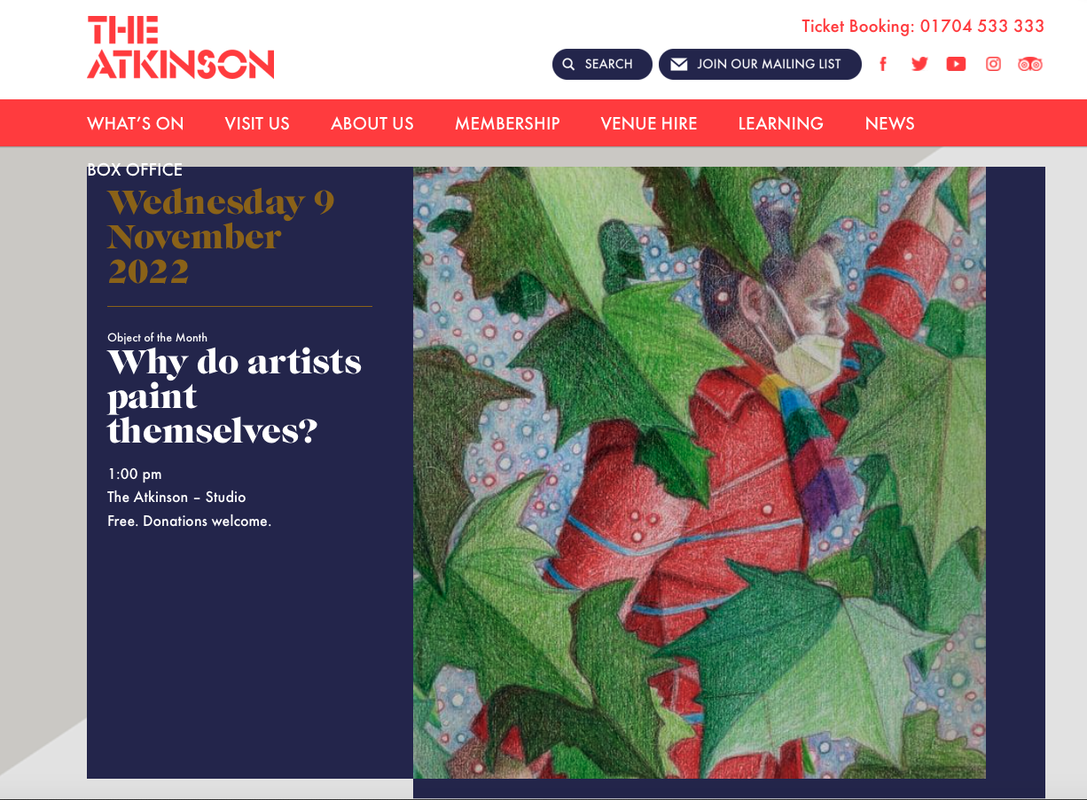

WHY DO ARTISTS PAINT THEMSELVES - A Talk by artist Nahem Shoa

The Atkinson - Southport October 2022 - March 2023

|

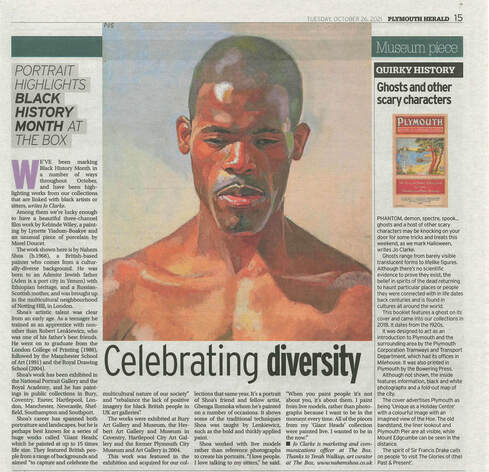

Now based in London, he studied in Manchester. Shoa has a long term commitment to representing people of colour.He strives to capture the unique skin colour that is individual to the sitter and not a racial stereotype. Shoa’s goal is to paint black skin as intensely as Lucien Freud painted white

|

Artists for over three thousand years did not make self-portraits and they only really began to do so in the 14th century. This was when the great artists stopped being anonymous craftspeople and became art superstars. That is why we all know what Frida Kahlo , Van Gogh, Picasso and Tracy Emin look like.

Through their Self Portraits, they have all become icons. Celebrity culture is a modern offshoot of this kind of immortality and intern has triggered our love of taking selfies. How we look to others has become more important than how we think and believe of ourselves. This talk explores the meanings behind some of the greatest Self Portraits from the 14th century to the present day and why they remain fresh and relevant, even now in the 21st century. The best self-portraits are some of the greatest art ever made because they are about the human condition and reveal profound inner truths about the artist, but also speak to our own unique humanity. |

Manchester City Art Gallery

|

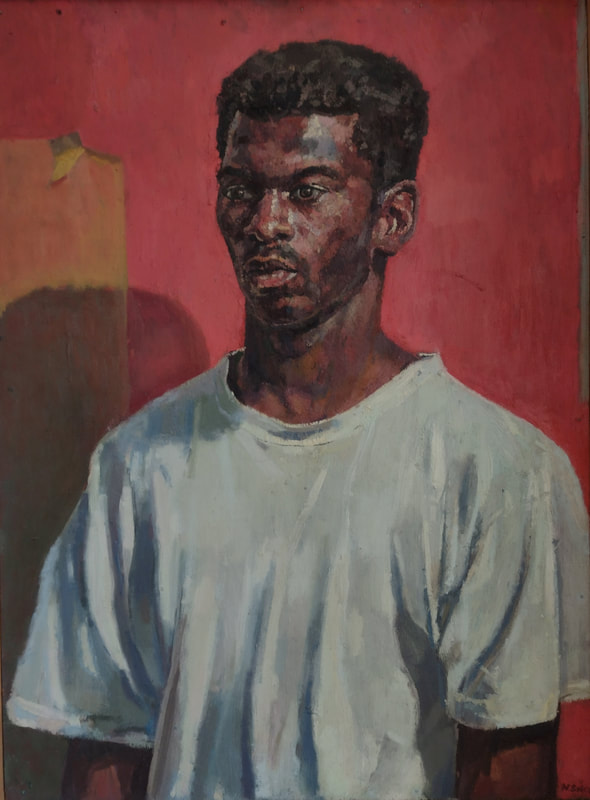

New acquisition: Nahem Shoa

Manchester Art Gallery is delighted to announce that a painting by Nahem Shoa has been gifted by the artist to the collection. Now based in London, Shoa studied in Manchester and this portrait was painted in his final year at Manchester School of Art and was exhibited in his degree show. The painting depicts Shoa’s childhood friend, the artist Desmond Haughton. Shoa painted the portrait from life at night after the college day ended. It took 2 months between the winter and spring of 1991 in Haughton’s studio in Hulme, Manchester and involved around 12 two-hour sittings. After finishing college, Shoa returned to London where he did one final sitting with Haughton to bring out more subtlety and presence from the portrait. Shoa has a long term commitment to representing people of colour. He strives to capture the unique skin colour that is individual to the sitter and not a racial stereotype. Shoa’s goal is to paint black skin as intensely as Lucien Freud painted white skin. This painting joins another smaller work by Shoa in the collection titled View from Hulme Flat c.1990. This was the view from Desmond Haughton’s flat, the location where the portrait sittings occurred. It shows the Crescents in Hulme shortly before they were demolished in 1993, a place where many of the city’s artists and creatives lived. |

During his successful career, Shoa has become well known for his Giant Heads, a series of portraits painted up to 15 times life size. He has generously donated many of his portraits of black or dual heritage people to British museums and galleries to rebalance the lack of positive imagery of black Britons in their collections. His work features in numerous collections including The Laing, Newcastle, The Box, Plymouth, Sheffield’s Millennium Galleries, The Herbert, Coventry, Southampton City Art Gallery, Bury Art Gallery, Ferens Art Gallery, Hull and the V&A, London.

My 1989 portrait of the artist Desmond Haughton, has been acquired by the wonderful Ferens Art gallery, Hull in 2022

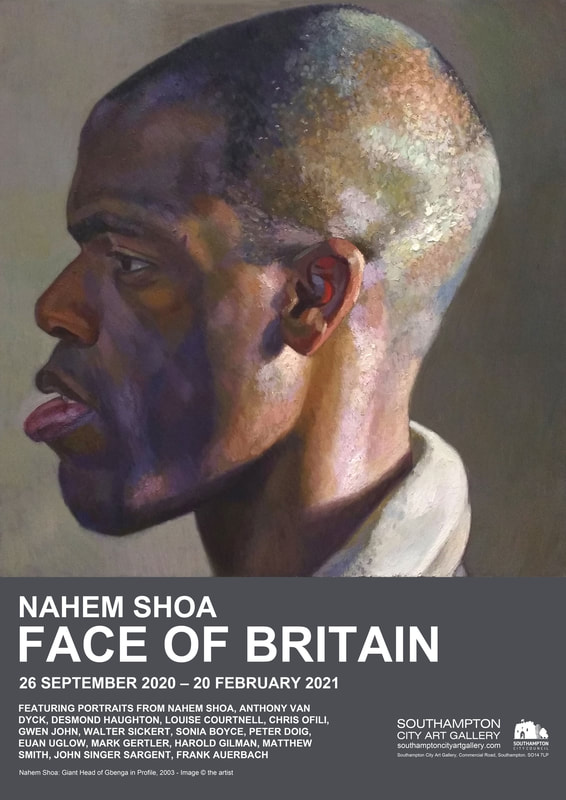

Face of Britain |

September 26 2020 - September 20 2021

|

|

|

|

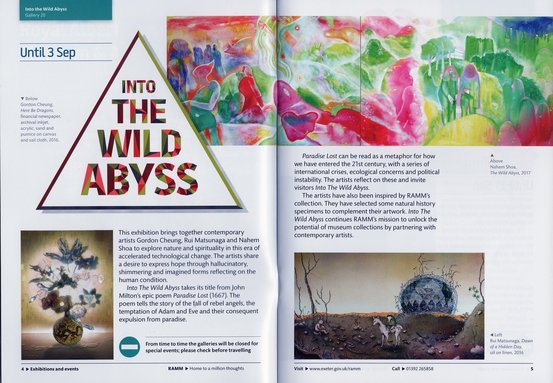

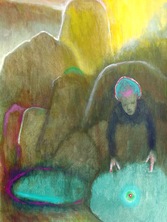

Into The Wild AbyssJune- September 2017 at RAMM - The Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery, Exeter.

Nahem Shoa with artists Gordon Cheung and Rui Matsunaga exhibit their paintings inspired by John Milton's epic poem, Paradise Lost. |

|

Nahem Shoa: The Cat Show 12 November – 17 December 2016

PAPER is an artist-led, commercial gallery based in Manchester and represents a range of emerging and mid-career artists whose practice is based around the medium of paper.

Nahem Shoa This was very tempting - Acrylic on Paper 40.5 cm x 30.5 cm 2016 |

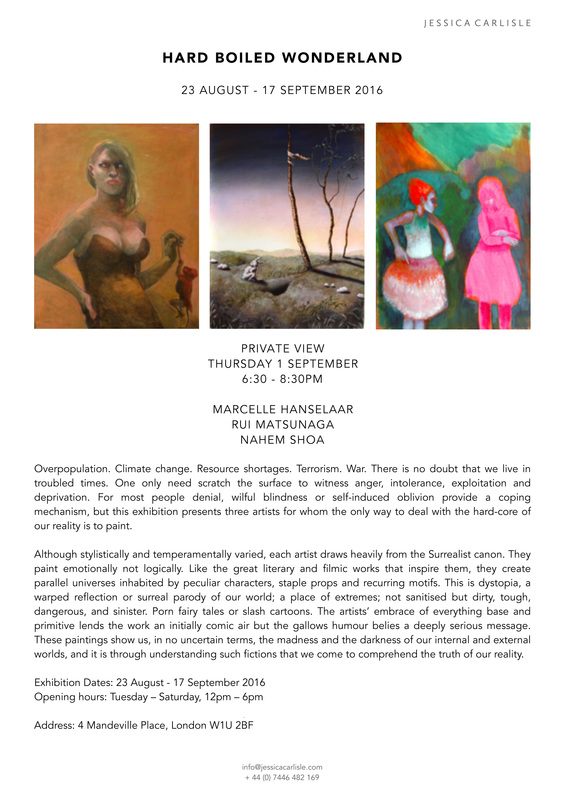

ARTISTS: Marcelle Hanselaar, Rui Matsunaga, Nahem Shoa

Nahem Shoa's recent work seen at the Jessica Carlisle Gallery.

BELOW IS A REVIEW OF THE EXHIBITION IN GALLERIES ART MAGAZINE

For the second instalment of Traction Magazine’s three-part interview series, Nahem Shoa shares the stylistic and conceptual influences behind his body of work in ‘Hard-Boiled Wonderland’ at Jessica Carlisle, London.

"There is something very timeless about your paintings, but titles such as ‘Coke Head’ and ‘Drug Dealers’ root them firmly within the grittier reality of contemporary society. Is there a politic agenda in bringing characters such as these - mostly ignored by art history - into the forefront of your paintings?"

I love the paintings of Giorgione and Titian that are set in early twilight, where shepherds and lovers sit in a still and timeless landscape. We have all felt this mood when in these kind of places and our souls yearn to be there. The real world is darker and more scary. Pretty nine year old children sell drugs for the Mafia in Sicily and across the word. My paintings try to convey both gritty reality and timelessness because that is how I see the world. I always steered towards subject matter that art history ignores and I feel deserves to be seen. Nahem Shoa

#nahem shoa #artist quotes #paintings

Susie Pentelow | Editor